Bang Your Gong!

A Guide to the Use of Gongs in Satanic Ritual

by Magus Peter H. Gilmore

In 1966, when Anton LaVey carefully crafted his concepts for ritual in his new religion, he was not beholden to any specific prior traditions. For the first time, he was inventing Satanism as a satisfying religious practice. Previously, Satanism was in the realm of horror fiction, intended to frighten people, or used as a term for anyone practicing what was deemed heretical by their accusers. Being fictional, it had no established standard liturgy nor rubric for ritual gestures. LaVey had experienced religious rituals performed by the generally accepted major sects of his day and found them to be tepid—primarily intended for passive audiences. The Sunday morning tent-show evangelists he often accompanied on the organ had “Hellfire and Damnation” rhetoric with its own built-in bombast, though noting the groveling congregants who had been “sinning” the prior night at the carnival where he also played was more to his interest. What might he have thought of a rollicking “gospel” service, with its exuberant singing and dancing—far more carnal than many Christian services? LaVey was a man who understood showmanship, so with Satanism he wanted to offer a stimulating alternative to what he saw as the ho-hum kneeling and praying that bored so many Christian believers. He was not impressed by the stilted “white magic” rites of the Rosicrucians and the seekers after The Golden Dawn. The nude, neo-pagan circle dancing, scourging, and charm-reciting that was part of the Wicca boom, he thought to be rather juvenile. It was time for his congregation of Satanist “unbelievers,” who embraced the flexible tool of ritual, to enjoy some gothic, exotic drama in their home chambers!

LaVey’s Early Gong Encounters

We know that Anton LaVey was an eager viewer of the cinema throughout his life. Being born in 1930, films during his youth were working hard to adapt existing properties towards entertaining the masses. He enjoyed the opulent spectacles that might at times depict strange locales and their fanciful beliefs and practices, quite in opposition to the staid services that the folks around him were attending. The FLASH GORDON (1936-40) film serials derived from the comic strips were popular during his youth. The sci-fi adventures of Flash, Dale Arden and Dr. Zarkov on the planet Mongo—dominated by the Fu Manchu-esque Ming the Merciless—caught his attention. While Ming’s sinister appearance certainly planted ideas for how LaVey would develop his adult look as High Priest of the Church of Satan, I suspect the use of gongs in the religious rites and court etiquette in those series also had an influence. On Mongo, the inhabitants worship the Great God Tao (rhymes with “Day-O,” not “Dow”), represented by a statue of Osiris that had previously been used in the Karloff film, THE MUMMY. Ming schemes to forcibly wed a drug-befuddled Dale, and the marriage is conducted by Tao’s High Priest (hmmmmmmm?); with 13 bongs on a ceremonial gong, they’d both be hitched. Flash naturally saves the day by interrupting the ceremony just before the final stroke. Gongs are also used in those serials to herald the arrivals of important visitors to court assemblies. LaVey absorbed the idea that the sound of a gong was an exciting and essential part of exotic religious and social rituals.

KING KONG (1933) was a massive hit and was seen far and wide. This movie elaborated on the earlier silent film,THE LOST WORLD (1925), in which the survival of prehistoric animals in remote locations made for an adventurous exploration. Skull Island, home to Kong, may have been the last remaining edge of a sunken continent, with a small peninsula separated by a cyclopean stone wall built by a vanished ancient civilization, intended to keep the humans safe from the wildlife beyond its massive wooden portals. King Kong was the alpha beyond the wall and the islanders would periodically offer one of their women as a “bride” to placate him. To let him know a “gift” was being presented, a truly massive gong atop the wall was struck by two men with beaters to send forth a summons for this powerful force of nature to make his appearance. The giant gong was a prop and an actual smaller, but quite sonorous, gong was recorded for the soundtrack. It certainly was and remains an impressive sight!

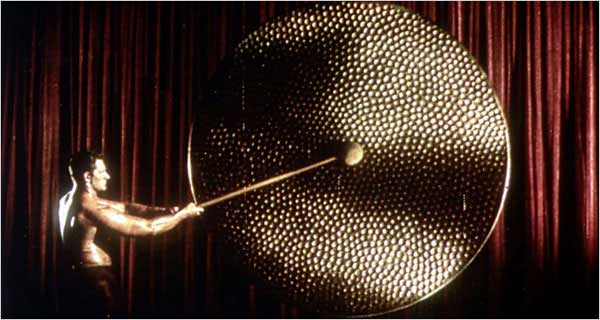

The Fleischer SUPERMAN cartoons (1941-43) were then rather ubiquitous, and certainly still worth viewing, as their dark deco designs are impressive. For the opening of each, there’s a brief litany explaining Kal-El’s powers and background, as onscreen a sparking fireball heads towards the audience. As it arrives, it bursts into the figure of Superman, arms akimbo in a confident pose. This is accompanied by a forte crash on a gong—thus the god-like orphaned alien superhero’s presence is marked by that exotic instrument’s resounding voice. Concurrently, the J. Arthur Rank Studio of England (1940s-60s) had a corporate emblem that was called the “Gong Man,” and their films’ openings included an image of a muscled man (wrestler Ken Richmond), stripped to the waist, swinging a mallet into a massive gong. The gong in the image was a prop, made of papier-mâché, but a real instrument was recorded to accompany that title insignia. This studio produced quite a variety of excellent films and some certainly were enjoyed by the observant, youthful Anton LaVey.

In his formative years, LaVey experienced gongs being used for three primary purposes: summoning, salutation, and celebration. And, in a more restrained mode with softer strokes, we now may include a meditation mode, as it has become a widespread use for this ancient Asian musical instrument.

Gongs in Pop Culture

Dinner gongs—often ornate, bossed gongs—were employed in upper class Victorian and Edwardian households (and in films depicting this “upper crust”), rung by the servants to summon the family and guests to the main formal meal of the day. At times, the ringing might also signal that it was time to properly dress for the upcoming dining experience. This may have arisen because, at the height of the British Empire, many exoticisms from its far-east territories were adopted in England, and Buddhist monasteries in those regions often used gongs—at times in other than round shapes—to summon the monks to their meals.

In slang terms, “kicking the gong around” was a vintage reference to the partaking of opium in what were typically Chinese owned and operated dens of iniquity. Cab Calloway’s sassy MINNIE THE MOOCHER makes it all quite clear. “Bang a gong” later became a euphemism for snorting a line of cocaine. So, beyond their connection to ceremonial use, gongs had an “edgy” connection with such libertine pharmacological indulgences.

And, not to be forgotten, from 1976-89, Chuck Barris’ amateur talent program, THE GONG SHOW, had a panel of three B-level celebrities who judged acts that went from the abysmal to the wonderful. The contestant had to survive being “gonged” by one of the judges. The fairly large chau gong suspended behind the judges when sounded ended the performances of the most egregious contestants.

A Primal Voice

Gongs are somewhat concave metal disks which usually have a turned-down edge—which can be curved, rather straight, deep, thick, thin, or even non-existent. They are suspended from a frame or stand by a strong cord so that they are free to resonate when struck by a mallet. Gongs are noted as being used in China for two millennia, so they are truly primal sound makers. Two primary types predominate. Flat-centered gongs, which typically are un-pitched, produce a wash of sound whose depth corresponds to the diameter and thickness of the disk. Gongs with a bump in the center—called bossed, nipple, or bell gongs—are pitched and their fundamental tone is a specific note above which there are resonating overtones, but no “splash.” These gongs tend to be rather thick overall, with prominent, extended edges, and the sustain of their sound after being struck is much briefer than their un-pitched cousins. The Javanese Gamelan ensemble includes an array of bossed gongs tuned to the notes of scales used in music from that region, so that melodies may be produced when striking them. Gongs, as well as cymbals and bells, are typically made of brass (an alloy of copper and zinc) or bronze (an alloy of copper and tin), the latter of which results in higher quality sounds being produced—more resonant with longer sustains to the ringing. These instruments are still made with these alloys. Paiste and Meinl both have a line of nickel-silver alloy “symphonic” gongs that are thinner, and more costly, but have very rich sound profiles. For clarity in classical scores, flat-centered un-pitched gongs are referred to as tam-tams, while the bossed gongs with specific pitches are called gongs. Tam-tams thus are gongs, but this term isn’t much used outside of classical music. There are other sorts of gongs, some shaped in other than a circular form, and others that are small and pitched and set in boxed frames to be played melodically. Today there are a number of artisans pushing the boundaries of what a gong might be, even to using new, experimental alloys. We are in the midst of a renaissance in world appreciation of these venerable instruments.

Gongs in Classical Music

LaVey was a natural musician and, in addition to absorbing evocative popular songs detailing human foibles and desires, he also drank deeply of the classical repertoire. He favored music of bombast in which one often finds this instrument being used to telling effect. In Western classical works, the first use of a tam-tam in an orchestral piece was by the French composer François-Joseph Gossec for his Marche Lugubre (1790). Hector Berlioz gladly took up its use and had this to say about it in his Grand Traité d’Instrumentation et d’Orchestration Modernes (1855)

The Gong

The tam-tam, or gong, is only used in compositions of a dirge-like character and for dramatic scenes of the utmost horror. When mingled in a forte with strident chords of brass instruments (trumpets and trombones) its vibrations have an awe-inspiring quality. No less terrifying in their lugubrious resonance are the exposed strokes of the gong, as Meyerbeer has demonstrated in the magnificent scene of the resurrection of the nuns in Robert le Diable.

Of course, this powerful and exotic sound became part of the soundscape of many composers and you’ll find it well used by Tchaikovsky, Mahler, Shostakovich, Respighi, Copland, and Rachmaninov—the finale of his first symphony finds the tam-tam essential. Puccini’s opera Turandot, set in China, calls for both bossed and flat gongs—a set of 13 were commissioned from a family in the consortium of Italian makers of cymbals and gongs called UFIP. The British composer Ralph Vaughan Williams often used tam-tams, but was inspired upon hearing Turandot to employ pitched gongs in the joyous finale of his Symphony No. 8.

Gongs in Satanism

With this extensive background in observing the use of gongs in religion, secular ceremony, music—both Western and Eastern, and film, Anton LaVey knew precisely what he wanted to use as an essential tool for the rituals he devised for his nascent Church of Satan. Here is what he said about them:

GONG:

The gong is used to call upon the forces of Darkness. It is to be struck once after the participants have repeated the priest’s words, “Hail Satan!” For the best tonal quality a concert gong is preferred, but if one cannot be obtained any gong with a full, rich tone may be used.

—The Satanic Bible (1969)

GONG:

Gongs are often hard to come by, as many members have discovered, especially ones that don’t sound like a hub cap when struck. Furthermore, a concert gong with a rich tone can often run into several hundred dollars. Rather than do without the brazen sound so highly desired in ceremonies, substitute a good large crash cymbal. After all, the cymbal and gongs are first cousins, and the cymbal originally was used for religious rites of antiquity. A fine Zildjian cymbal can be obtained for but a fraction of the cost of a gong of comparable quality, and suspended from a leather thong or mounted on a stand, will give forth sounds guaranteed to invigorate the senses.

—Some Helpful Hints on Developing a Satanic Ritual Chamber in the Home (1970)

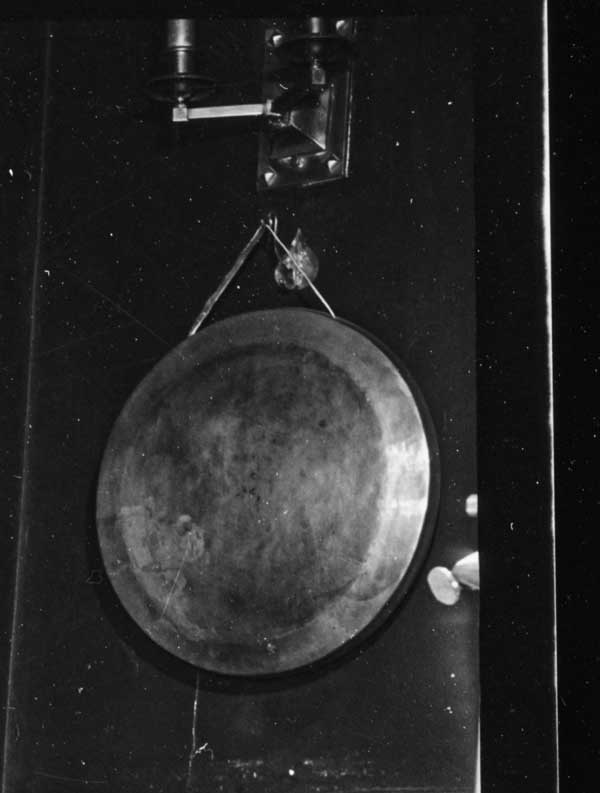

LaVey himself owned his gong before he founded the Church of Satan. It was hung from a wall bracket to the right of the fireplace, with its mallet hung to the right of it, in the front parlor of his California Street Black House—before it became Satanism’s first famed ritual chamber. From the images of it, the diameter seems to have been about 20-22 inches, and from the sound it produces—a quick “splash” and a short sustain, with some deeper tones because of its edge, it was likely made of brass. The caption for an image of him posed in front of it from THE DEVIL’S AVENGER states it is a brass gong, and it is possible that LaVey obtained it via some venue in San Francisco’s Chinatown district. Unlike today, wherein any sort of gong imaginable is available online, back then, gongs were rare and costly objects. They are, after all, hand made, musical instruments.

Suggestions for your Ritual Chamber

Today, anyone seeking to purchase a gong of any sort has an amazing array of choices available—highly varied types made in several countries, in sizes, from minuscule to massive, and certainly a wide assortment of prices. One thing to bear in mind is that, being plates of hammered metal, the larger the gong, the heavier it is. For many types, if you keep to smaller sizes, you can have a table-top stand so they can sit on your altar or a table placed near it. Larger gongs, depending upon their weight—perhaps up to 24 inches in diameter, can be mounted on a wall bracket—a larger plant hanger bracket can do, so long as the screws holding it in place are anchored into a stud in your wall. Gongs will swing from front to back when played, so they must be far enough from the wall so that the lower edge will not crash into it when given a vigorous blow. Once you go beyond 24 inches, a sturdy floor stand is required. Thus, you select your gong based on your budget, and the space you might have in which it will be placed. Smaller gongs that can fit atop your altar are more bell-like in effect, but with a bit of a deeper sound. However, if you want a grand, emphatic splash, 20 inches and beyond is what I’d suggest.

When gongs are forged, they emerge coated with an oxidized layer, and it is lathed-off to create a shiny surface. The ratio of oxidized-to-lathed areas creates the sound profile for each type of instrument. They are then carefully hammered by expert craftspersons to attain impressive sounds and tunings. China is the ancient source, in the Wuhan environs, and you’ll find unique styles also made in Vietnam, Nepal, India, Malaysia and Thailand. As mentioned above, UFIP in Italy were famous for their metallic percussion instruments and today two German companies, Paiste and Meinl (founded by a former Paiste craftsman) are world famous for their high quality percussion instruments. Paiste originated what they call a “symphonic” gong, which is a bit thinner than the traditional Chinese instruments, but, via careful hammering, these produce sounds with very rich overtones. Here are three types of Chinese bronze gongs which I think are splendid for your ritual chambers.

Feng Gongs

One of the most useful, popular, and affordable types of gongs are the feng (wind) gongs, which range from under one foot to over 6 feet in diameter. Their surfaces are fully lathed so they have a beautiful sheen and they have no edges. This makes them lighter in weight compared to other types of gongs of comparable diameter and they are made to have the greatest “splash” of sound when played. While they have some deeper tones when struck close to the center, when struck just outside the central circle (generally the “sweet spot” for most gongs) the sound “blooms” quickly into a rushing “splash”—considered to be like the rising wind or a lion’s roar. This type of gong has been frequently used by bands of various sorts for a century. My first gong is one of this type—just under 22 inches in diameter—purchased during my college years. I required one for my chamber works, as one of the musicians I wrote for was a percussionist and the NYU gong to which we had access was a battered, oxidized chau with rather miserable, attenuated sound. My friend would borrow my gong for performances of Respighi’s PINES OF ROME and Copland’s FANFARE FOR THE COMMON MAN (honoring the soldiers fighting during WWII). These days, a gong of this sort and size can be had for just under $150, and the sound you get is very dramatic. Also, this type of gong responds well and quickly, so even the novice or non-musician can get a very satisfying sound from one. These are often light enough to mount on a bracket, and they also can have a handle attached to the suspension cord so one can swing them after being struck to produce an interesting variant in sound.

Chau Gongs

The traditional Chinese gong, with a dark central circle and edge, is called a chau gong—typically what is intended when a score calls for a tam-tam. These have an excellent, but lesser, “splash” and deeper tones at the same diameters as the feng gongs. They are heavier as they are a bit thicker, and they require a heavier mallet to evoke the best sounds. The chaus “splash” more slowly than the fengs and have less high overtones. These are the sort of gongs you’ll see used by many symphony orchestras—often in the 30-36 inch diameter size. That is a great all-purpose size range and works for most symphonic works. This big a gong can easily fill a concert hall when played, so might be overkill for the home chamber. Mahler called for two tam-tams in his Symphony No. 2, one each of high and low sounding range, and using a feng with a bigger chau, or two sizes of chau, can accomplish what this score calls for quite well.

Dark Star Gongs

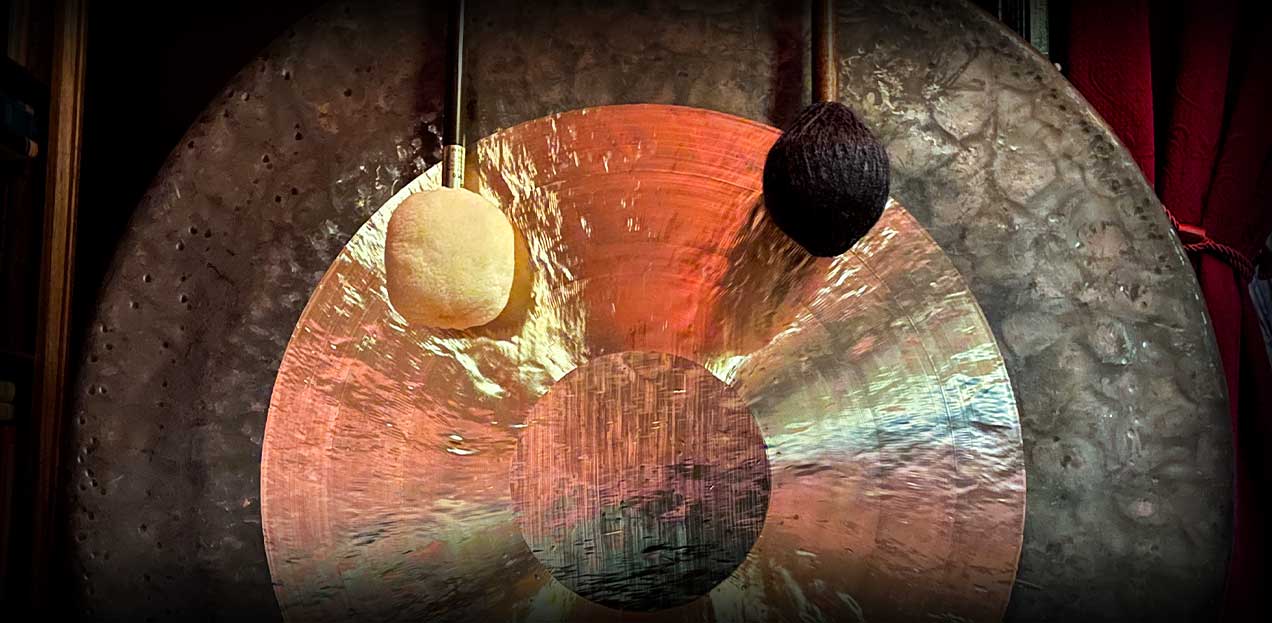

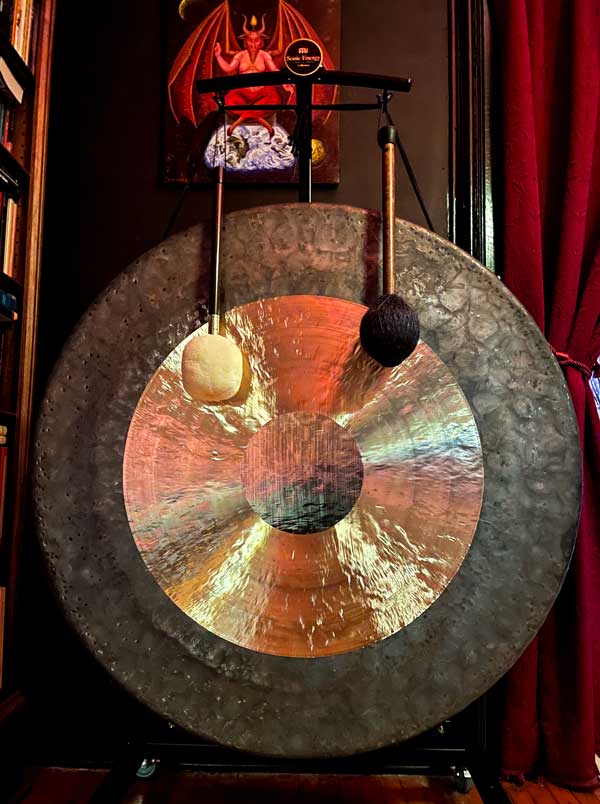

A cousin to the chau gongs, the “Dark Star” gong, has a wider oxidized band at the edge and is thicker and heavier than the same sized chau. The central circle is fully lathed so that it can have a musical “splash,” though less of one than a comparable chau. I am an aficionado of low frequency sounds—deep bass drums with loosened heads sounding like thunder, giant taiko drums, as well as those 32 foot organ pipes (16 Hz) and those ultra-rare 64 foot pipes (8Hz) which provide a subsonic rumble that is extraordinary in its sense of evoking a void or an abyss by being felt in one’s chest more than being heard. These Dark Star gongs are thus my preferred type, as they produce really deep tones compared to the same sizes of other gong types, though they take a bit more work and heavier mallets to evoke a full “splash” that tears up through the higher frequencies. For the celebration of my 20th anniversary of becoming the High Priest of the Church of Satan, I was gifted by our members with a splendid 40 inch Dark Star gong, which now roars from the ritual chamber of my Black House along with its smaller, brighter brother.

If you peruse a gong selling merchant’s site, like the extraordinary Gongs Unlimited, you’ll find many other types of gong, with varied patterns of lathing, tunings to specialized frequencies, some with fully oxidized surfaces, varied shapes, and plenty of ornate, bossed gongs in elaborate frames that I consider more pieces of decoration than musical instruments. While my Surtur feng gong came from a music store off of Broadway in Manhattan in the upper 40s, Behemoth was from Gongs Unlimited, who also have all of the accessories you need—stands, mallets, polishing liquids, and even carrying cases.

Playing Your Gong

Since gongs are activated by the kinetic energy of the mallet impacting them, it is important to purchase a mallet of the proper weight to initiate your gong’s vibrations. Too light and it won’t really get it going; too heavy and you’ll just be pushing the gong rather than activating it. A diligent gong merchant can offer you suggestions for a proper basic mallet to accompany the gong you select. Softer mallets have less of an impact on the surface of the gong, and so you’ll not hear that “attack” sound that a harder mallet will produce.This is important when you are doing a more meditative ritual and want to bring forth the deepest tones of your instrument. When striking a gong, it is of crucial, particularly for larger and deeper toned gongs, to at first “prime” them with several light taps to initiate vibrations—too light to be audible. Thus, when you make that sounding strike, it will rise to its full “bloom” of overtones. Also, as musical instruments, you must learn how to properly strike them—and that takes some practice. You don’t ever want to hit one as hard as possible, as that could dent or crack the disk and ruin its sound. Start with a gentler impact, just off the central circle, which will coax out the deeper tones, then increase the strength of your strikes and you’ll find with bronze gongs, and other more refined alloys, that you can achieve powerful volumes with vigorous, but not violent, striking. And these gongs will resonate for a long time, the initial splash slowly decaying into a deeper, lasting ringing vibration.

One can also purchase friction mallets, which are silicone or rubber tipped mallets which one holds near the head and which are dragged across the surface of your gong. These can produce a sort of “whale song” assortment of sounds, depending upon the length of the stroke across the surface and the amount of the mallet head in contact—the smaller ones make higher pitched sounds. One can try varied mallets and strike the gong in places other than the sweet spot to get a wide variety of sounds. Two mallets are excellent for creating a roaring crescendo, when struck alternately with ever-increasing force. On smaller gongs this can be done on the front surface, but with larger ones, two soft and heavy mallets impacting on the front and the back in a controlled succession of increasingly stronger blows can make a sound like an approaching freight train. Messiaen uses this to great effect in his ET EXPECTO RESURRECTIONEM MORTUORUM—one of the best pieces for hearing brilliant use of tam-tams, tuned gongs, tubular bells, cowbells, woodblocks, brass and woodwinds. Gongs can also be bowed, with the sort of bow you might use on a viola or cello, so long as it is well-rosined. Bow on the edge of the gong in a steady movement and you’ll hear a range of wonderfully weird harmonics. Stravinsky called for scraping the metal beater for a triangle across the surface of a tam-tam for a cutting sound in his Rite of Spring. Some contemporary pieces have even called for lowering a struck gong into a tub of water, which brings forth evocative pitch-bending. Finally, when gongs aren’t damped with a draped cloth or otherwise muffled (hanging the mallet so that it rests against the surface can somewhat mute it), they do react to surrounding sounds. Thus, one can sing, chant, or even howl into a gong and discover what the pitches in your voice bring forth from it. Like a wolf baying at the full moon, take some time to howl into your gong and listen to its responses—I’m sure you’ll find them stimulating. The full moon howls back!

Do not forget to polish now and again particularly the lathed ares of your gong, as ongoing oxidation can alter and restrict the sound it makes. Any polish suitable for bronze or brass or whatever alloy your gong is made from will do. And some gong merchants will offer specific polishes which are quite useful.

Since gongs each have their individual voices, it is enjoyable to spend time with them, learning how to bring forth their rumbles, keening calls, and roars. Your gong will be a unique instrument, and may feel rather “alive” in the various sounds it can produce. Listening for a possible name in its voice can enhance your connection to the instrument, especially as you will dedicate it as a ritual tool for your Greater Magical efforts. My feng gong I’ve named Surtur, for the fiery quality of its sound, and the rumbling Dark Star gong is named Behemoth. Your gong will feel like far more than just an inanimate object—it will become a “living” presence in your rituals and meditations, and you can honor it with a name that seems to capture its unique essence for you.

Live Music in Ritual

The Satanic Ritual chamber, a domain for rousing your passions, benefits from the use of myriad sounds and music to enhance one’s emotional responses therein. Currently, we listen to most things via recordings, so speaker systems are giving us representations of acoustic instruments, and, as technology has advanced, ever better sounding and in more compact forms. Today’s “smart speakers” operated via voice commands, are a boon to solo or group rites as you can vocally summon up appropriate music during the course of a ritual. This is much easier and more flexible than when we had to use taped sounds (reel-to-reel or cassette) to provide a ritual’s accompaniment and interrupt the ritual to access the tape deck’s controls. While we would make extended tapes to run for the entire rite, when you wanted something specific to follow the flow, one had to access the “start” and “stop” switches.

Acoustic instruments, in addition to the gong and bell, are a natural addition for being played in your chamber—they are exciting as their full resonance is unadulterated. The creative Satanist can find use for practically anything that they or their fellow participants can play. Also, one can use the ritual space as a place for practice and meditation—simply ring your bell the traditional nine times at the beginning and end of your session, and let your thoughts and expressions wander as the notes flow from your instrument in a manner that provides introspection or catharsis. One can play a composition or simply improvise.

When viewing SATANIS: THE DEVIL’S MASS, you will note that, in addition to the organ music that LaVey favored—he was a professional organist—a drum is used to accentuate a sequence wherein rising waves of “kundalini” energy are considered to be evoked. The gong in the chamber is not struck during the filming of SATANIS and I suspect that it would most likely have overwhelmed the microphones being used to capture the live sounds of the rituals being performed. Gongs can produce very powerful sound waves, so care—as well as some distance—is required when capturing them in a recording. In classical performances, tam-tams and gongs are usually placed to the rear of the orchestra as they and the rest of the percussion battery can readily project over the other orchestral instruments.

Your Ritual Companion

Today, we are in the midst of a new “Bronze Age” with an availability of a vast variety of gongs crafted around the world, ready for your purchasing. The “New Age” culture during the 1970s cultivated an embracing of Eastern philosophies and practices and this has lead to today’s current vogue for “Sound Baths” and “Gong Baths” as adjuncts to yogic or other meditational practices. Gongs, bronze (or crystal) singing bowls, as well as bells are used to create a wash of reverberant sound intended to relax or focus the mind and body of the participant. You’ll find a plethora of people online who call themselves “gong masters” running these sessions. While Satanism primarily embraces gongs for dramatic punctuation of ritual, they can also serve in this more meditative means, particularly in a rite such as “The Statement of Shaitan” from LaVey’s The Satanic Rituals. As written, a gong stroke is used to punctuate the silence in between the readings from the Al-Jilwah. One could additionally use their gong while the passages are intoned, with mild strokes evoking the deepest of tones, then striking with a more forceful blow between these passages.

When seeking the gong you wish to purchase, if looking online, visit a merchant site that presents sound files or videos of the instruments they offer. Listen to these with your best headphones, or with a superior sound system. It is best to listen to the gongs within your budget—and remember that you will need to buy at least one proper mallet and perhaps a bracket or stand as well, so their costs should be considered. Examine the gong’s appearances, and appreciate their hand-hewn aesthetics, but most importantly experience the sounds produced. The gongs that conjure for you a sense of awe and excitement would be the candidates for your adoption.

Once received, treat your gong with respect as it is one of civilization’s oldest musical instruments. You are inviting it into your ritual space to work with you, in contemplation, celebration, and rites of Greater Magic. Listen carefully and you might even find a name arising from its mysterious voice to be used for this venerable speaking entity. Even if you are a solo practitioner, your ritual practice will never again be truly solitary, for your gong will be your friend and companion as you create that stimulating time-out-of-time that is known to us as Satanic Ritual.

Black House Gong Audio

We welcome you to enjoy and use in your own rituals, the following gong sound files from both past and present Black Houses. We would like to give special thanks to Magister Gene Lavergne for his assistance in mastering the audio.

Portrait

Peter H. Gilmore

High Priest of the Church of Satan

We Are Legion

A Moment In Time

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

SUPPORT THE

CHURCH OF SATAN!

There are many ways you can support the Church of Satan. Visit our support page to learn how.

navigation-topper