Godzilla

by Magus Peter H. Gilmore

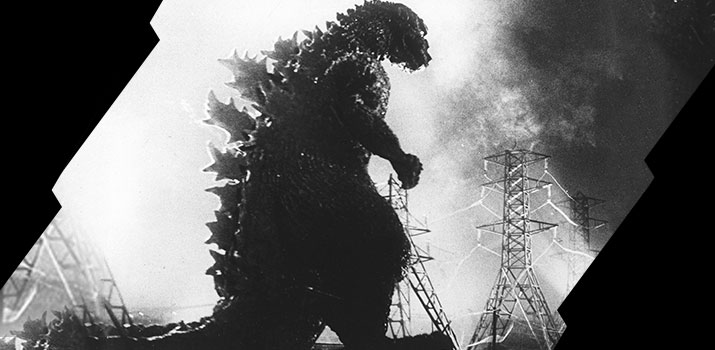

Named “Gojira” by his Japanese progenitors in the eponymous 1954 filmed parable, Godzilla in his most potent depictions touches on something very primal. Hell, he grabs it by the throat.

Jung’s concept of archetypes assists in understanding the power of his imagery. That massive figure, towering over the works of mankind and destroying them with ease, embodies nature at its most fearsome. He personifies the unstoppable hurricane, tornado, tsunami, earthquake, volcanic eruption, fused with man’s most dramatically destructive efforts—nuclear detonations. As a child watching footage of the various nuclear explosions, they held a gorgon-esque ability to freeze consciousness with actual awe. They are amongst man’s grandest achievements. Quite telling about us that they are destructive, poisoning what is not obliterated outright, not constructive. Time erases our edifaces, but the half-life of atomic residue leaves a fingerprint that is nigh indelible.

Godzilla anthropomorphizes Nature by giving a consciousness to such vast and terrible powers that dwarf us, showing us how truly insignificant we are, personally and as a species. And that such a threat could possibly focus on us intentionally, rather than being something mindlessly passing dreadfully near, amplifies its might. Godzilla’s presence emphasizes ephemeral humanity.

When observing the cataclysmic nature of the cosmos around us, we may also experience that feeling. Primitive societies found similar emotions arising when contemplating aspects of their mythologies. H. P. Lovecraft evoked this “cosmic dread” in the best of his fiction. Godzilla inhabits our most potent and ubiquitous contemporary art form: cinema. He looms in what is the repository of our cultural consciousness and is a globally recognized symbol. Hence he may be the most vivid embodiment for 20th and 21st century folk of that sensibility of our fragility.

to such vast and terrible powers

that dwarf us…”

Spiritual philosophies generally propose transcendence of man’s insignificance by positing that we might, through submission to a God or gods, gain immortality. Carnal philosophy accepts our transitory nature, showing how precious is our existence because of its brevity, suggesting that we make the most of what little we have, much as can be felt when contemplating the fleeting beauty of a flower…or when witnessing the destruction of our creations by the puissance of Nature. Carpe diem. Godzilla’s lesson: Nature can and does shrug us off, and might do so more readily if we have the hubris to upset its balanced progressions.

Over time, Godzilla morphed into a force that was turned from either chilling indifference or active hostility to humans to one that could be harnessed for our own ends. From a menacing black silhouette backlit by a sea of flames, he was diluted by the 1970s into an amicable mascot and savior of the Earth. The original concept was too disturbing and had to be palliated—from terrible grandeur to comic cuddliness. That is not surprising, since we tend to think that we might possibly find ways of conquering Nature, taming its mechanisms for our benefit. We conceptually lessen monumental aspects of existence to give us comfort. But Nature to be commanded, must be obeyed. Humans might try to reduce the vastness of the Universe, shunning its significance, but it is inexorably present when we look out from our small planet. The cosmos cannot be denied. And so Godzilla keeps returning as a dark reminder of that principle. The Japanese returned to far more grim iterations in later films.

It seems, from what I’ve read on line, that Gareth Edwards’ currently in production Godzilla film may be approaching this character with proper respect, inspired by the original Japanese version, but also informed by significant subsequent films in both philosophy and design. From statements he has made in promotional interviews, he seems to understand what it can potentially call forth. The sort of resonance captured by the original GOJIRA of 1954 could once again be rendered in a manner suitable for contemporary tastes, creating what might be perceived as a secular religious experience. When entering Canada to begin principal photography, he was told by two customs officials, who recognized who he was and why he was there, “Don’t fuck it up.” I echo that sentiment. Emmerich and Devlin missed the essence of Godzilla in their 1998 movie, for the most part remaking THE BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS (1953) rather than the deeper Toho film it inspired. It is time for Hollywood to render unto Godzilla what is his due.

That the English transliteration of GOJIRA became GODZILLA made inadvertently blatant the intention of the original filmmakers. They crafted a movie that would shatter complaisance through the rendering of a “wrathful” aspect of nature—what our species has long had recourse to naming as deity. Godzilla emerges from roiling abysses of human thought, seeking eternity in his recurrence. Again he rises, for we too are part of Nature, and so he is of us. Hail Godzilla!

Portrait

Peter H. Gilmore

High Priest of the Church of Satan

We Are Legion

A Moment In Time

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

SUPPORT THE

CHURCH OF SATAN!

There are many ways you can support the Church of Satan. Visit our support page to learn how.

navigation-topper